With its buildings carved into the vibrant sandstone cliffs and mountains of the southern Jordan desert, Petra was once a thriving cultural and economic hub in ancient times. But the city was later abandoned and left to ruin, remaining “lost” to the Western World until it was rediscovered in the early 19th century. Today, this UNESCO World Heritage Site attracts visitors from all over the globe. You may even recognize it from the scenes that appeared in the 1989 blockbuster Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. If a visit is on your bucket list, start by discovering the fascinating history of Petra, Jordan’s “Lost City.”

A Hub for the Ancient Nabataeans

From the fourth century BCE, Petra was the capital of the Nabataeans, and its strategic location helped their civilization flourish, putting them at the center of trade throughout the Middle Eastern region. Its narrow canyon entrance also served as a natural fortification that protected it from potential attacks.

With the sale of goods, such as spices, the city’s population grew rapidly — it’s thought that up to 30,000 people could have once lived there. Everything went swimmingly until the Romans muscled in on Petra in 106 CE and swallowed it up into their own empire. Trade continued, but not at the same level as before, and an earthquake in 551 CE was perhaps the final nail in the coffin for this city in decline.

It’s hard to imagine how the desert site we see today could ever have supported such a large settlement. But the Nabataeans knew that for their city to have any chance at success, they had to solve the thorny issue of water. Carefully conserving precious water in this desert environment was a given, but they were also masters of irrigation, creating a clever system of channels and dams to reroute water from the surrounding mountains. The cisterns they used to store water also helped keep it from being lost in the flash floods that were — and still are — a relatively common occurrence in the area.

A Swiss Explorer’s Discovery

For centuries, all except the local Bedouin people forgot Petra — its tombs were abandoned and buildings fell into ruin, hidden by the surrounding canyons. Then, in the early 19th century, a Swiss explorer named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt set off on an expedition in search of the source of the River Niger. In preparation, he’d studied Arabic at Cambridge University and then honed his vocabulary on the streets of Aleppo in Syria.

In 1812, on his way to Cairo, he heard rumors from locals of secret ruins of a grand city in the desert, so he hired guides and disguised himself as an Arab to gain access to what was considered a sacred place, forbidden to Westerners. They brought him to Petra. However, wary of pushing his luck too far, he didn’t stop to excavate. Five years later, Burckhardt died of dysentery in the Egyptian capital, but his “discovery” paved the way for future exploration of the site.

Some reports suggest that archaeologists have excavated as little as 15% of Petra thus far. Visitors enter through a narrow slot canyon known as the Siq and then amble along a street lined with tombs. The path leads to a temple called Al-Deir, or the monastery, reached by climbing more than 800 steps.

Impressive as the site is, however, that hardly scratches the surface. As recently as 2016, archaeologists discovered a previously unknown monument at Petra thanks to the magic of satellite imagery. It’s thought the huge platform, measuring 184 feet by 161 feet and flanked on one side with columns, could be more than 2,150 years old, based on fragments of pottery found nearby.

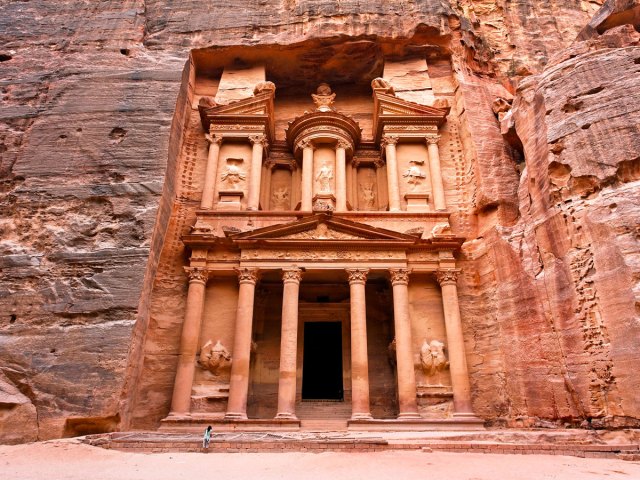

Petra’s Famous Rock-Carved Treasury

Perhaps the most familiar sight in Petra is that of its famous tomb, known as the Treasury or Al Khazna. Constructed sometime in the first century CE, the spectacular building is half carved into the surrounding sandstone and soars 130 feet above the desert. Appearing in a famous scene in the film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the treasury features intricate and well-preserved Hellenistic architectural details covering its two-story facade, which is crowned by a giant funerary urn.

Interestingly, the urn above the treasury is riddled with bullet holes. They offer a clue as to what was hidden inside this imposing facade. According to sources, such as Burckhardt’s diary entry of his first encounter with Petra, it was a long-held belief among locals that the urn contained hidden gold; in fact, it is made of solid stone. The urn is badly damaged as a result of those gunshots but a breathtaking sight nonetheless.

Petra’s Other Nickname (and Little Sister)

Petra’s abandonment led to its nickname of the “Lost City,” but you’re also likely to hear it referred to as the “Rose City.” The nickname refers to the reddish-pink sandstone cliffs, but it originates from a poem written by an English cleric named John William Burgon. The poem won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for Poetry in 1845, awarded by Oxford University.

Although Burgon had never set eyes on Petra, he wrote: “Match me such marvel save in Eastern clime, a rose-red city half as old as time.” The nickname stuck, and we’ve referred to Petra as the “Rose City” ever since. The color of the rock changes as the sun goes around the horizon, with the reddish hue most noticeable at sunset.

Meanwhile, even ancient cities had suburbs, and Petra’s was called Little Petra. While most of the action took place in the Nabataean capital, visiting traders would have probably found accommodation in Little Petra, perhaps close to some of the city merchants’ own homes.

Abandoned after the Nabataean decline, it remained largely hidden until archaeologists started to uncover its rock-hewn dwellings, water channels, and wall paintings in the 1950s. These days, few tourists visit the narrow space where Little Petra sits, as it receives little direct sunlight — a fact that is perhaps hinted at in its name, Siq al-Barid (Cold Canyon). Nevertheless, the treasures its sandstone reveals, such as the Painted House, are well worth the trek.

More from our network

Daily Passport is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.