Did you know that Big Ben isn’t actually the name of the London clocktower? Or that the Great Wall of China is made, in part, of cooked rice? Or that the Empire State Building was originally intended to disembark blimp passengers at its tip? The most famous landmarks around the world endure thanks to wild, surprising backstories. Ahead, learn some of the most fascinating facts you didn’t know about 16 of Earth’s most iconic spots.

Christ the Redeemer – Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

Sitting atop 2,300-foot-tall Mount Corcovado in Rio de Janeiro, Christ the Redeemer stands as a symbol of strength with his arms wide open over Guanabara Bay. But the 98-foot-tall structure with a 92-foot arm span isn’t immune to one major force of nature: lightning strikes. On average, the statue endures about three to five bolts a year, which are typically harmless. But in 2014, a direct strike broke off a piece of the Redeemer’s right thumb and damaged its head during one of Brazil’s most terrifying electrical storms in which 1,109 bolts were recorded in just three hours. During the repairs, more lightning rods were placed to prevent future damage.

Big Ben – London, England

When we think of Big Ben, we tend to think of the 314-foot-tall stone clock tower that rises from the Palace of Westminster on the bank of the Thames River in London. But in actuality, Big Ben is the name of just one of the bells inside, which was first struck on September 7, 1859. Of the five, Big Ben is by far the heaviest, weighing about 15 tons (the hammer itself is 440 pounds!), while the other four (which are called quarter bells) range from about one to 4.5 tons. The mighty bell strikes in the tone of the musical note E, as does the third quarter bell, while the first is a G, the second is an F sharp, and the fourth is a B.

Big Ben’s official name is actually the Great Bell of Westminster, but its nickname is believed to hail from Welsh civil engineer Sir Benjamin Hall, who was president of the Board of Works when the bell was cast. As for the tower itself, its name was the St. Stephen’s Tower until 2012, when it was officially changed to Elizabeth Tower to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s 60th year on the throne for her Diamond Jubilee.

Eiffel Tower – Paris, France

Many people assume the Eiffel Tower is made of black iron, but the Paris landmark is actually brown — a shade called marron glacé, to be exact. Marron glacé translates to “candied chestnuts” in French, and the color was named after the nutty brown hue of the French treat. The 1,062-foot-tall wrought iron structure has been painted the neutral tone since 1968. But that wasn’t its original color. The tower was originally painted a hue called Venice Red, which was a reddish-brown color that contained red lead called minimum in order to prevent the paint from eroding. In fact, the Eiffel Tower gets a new coat of paint every seven years to help preserve it — a plan initiated by Gustave Eiffel, the tower’s architect.

The shades of the Eiffel Tower have changed over time, with the original reddish-brown in 1889 alternating to ochre-brown in 1892. In 1899, the Eiffel Tower received a yellowish-brown makeover, before being repainted shades of tan in the early 1900s. If you look closely at the tower, you might even recognize that the current shade of brown is slightly darker at the bottom of the structure than it is at the top. This is so the Eiffel Tower appears to have a consistent tone from a distance.

The most recent repainting began in early 2021 and is expected to be completed ahead of the 2024 Summer Olympic Games in Paris. This time, the Eiffel Tower will be painted gold and stripped entirely of its old paint layers — a sparkling look that Gustave Eiffel envisioned himself when designing the structure. The golden Eiffel Tower was intended to echo the many golden limestone buildings throughout Paris.

Great Wall of China – China

Sticky rice is a staple of Chinese cuisine — yet when scientists at Zhejiang University were researching what was in the mortar used to build the Great Wall of China, they were surprised to find the cooked grain among the limestone-and-water mixture. As it turns out, those who built the series of walls across 13,000 miles (that’s right, the Great Wall isn’t actually one contiguous wall) over the course of 2,000 years found that the sticky rice-and-limestone mortar combination gave the paste more stability and a stronger hold — a formula invented during the Ming Dynasty.

Though that seemingly tall tale turned out to be true, another popular myth — the fact that you can see the Great Wall from space — doesn’t stand on such solid ground. Astronauts have said that from that great of a distance, the wall supposedly blends into its surroundings. The lighting also has to be just right for the wall to be seen.

Empire State Building – New York, New York

A blimp tethered to the top of the 1,235-foot-tall (or 1,454 feet tall if you count the spires and antennae) Empire State Building seems like something you’d only see in a movie, but it was an actual idea at one point. In 1929, the building’s investors said they would boost the tower’s height by 200 feet to beat out the nearby Chrysler Building. But the purpose of the extra height was to create a mooring mast so that a blimp could attach there for passengers to disembark into a private elevator and arrive on the streets of Manhattan within seven minutes.

While the plan was deemed unsafe due to intense wind, a small airship did tether itself to the top of the tower for a few minutes in 1931. A Goodyear blimp delivered a stack of papers onto the rooftop as part of a publicity stunt. And in 1983, an inflatable, eight-story-tall King Kong was attached to the top of the building for the film’s 50th anniversary — though the stunt didn’t last long, because the balloon developed a hole in its left shoulder.

Golden Gate Bridge – San Francisco, California

Did you know that the fog in the San Francisco Bay played a major part in the design — and purpose — of the Golden Gate Bridge? For starters, the bridge’s official color known as “International Orange” was selected for its ability to stand out among the thick clouds. But another major purpose of the bridge is to help direct the fog as it passes up and over the structure.

Foghorns have also been mounted on the Golden Gate since it opened in 1937, and are located in the center of the bridge and on the southern end at the tower pier. And the foghorns are usually blasting — often for an average of 2.5 hours a day. In March, the foghorns only sound for half an hour, but the foghorns can sound for more than five hours — and in extreme cases, for days on end — in summer, when the fog is particularly dense.

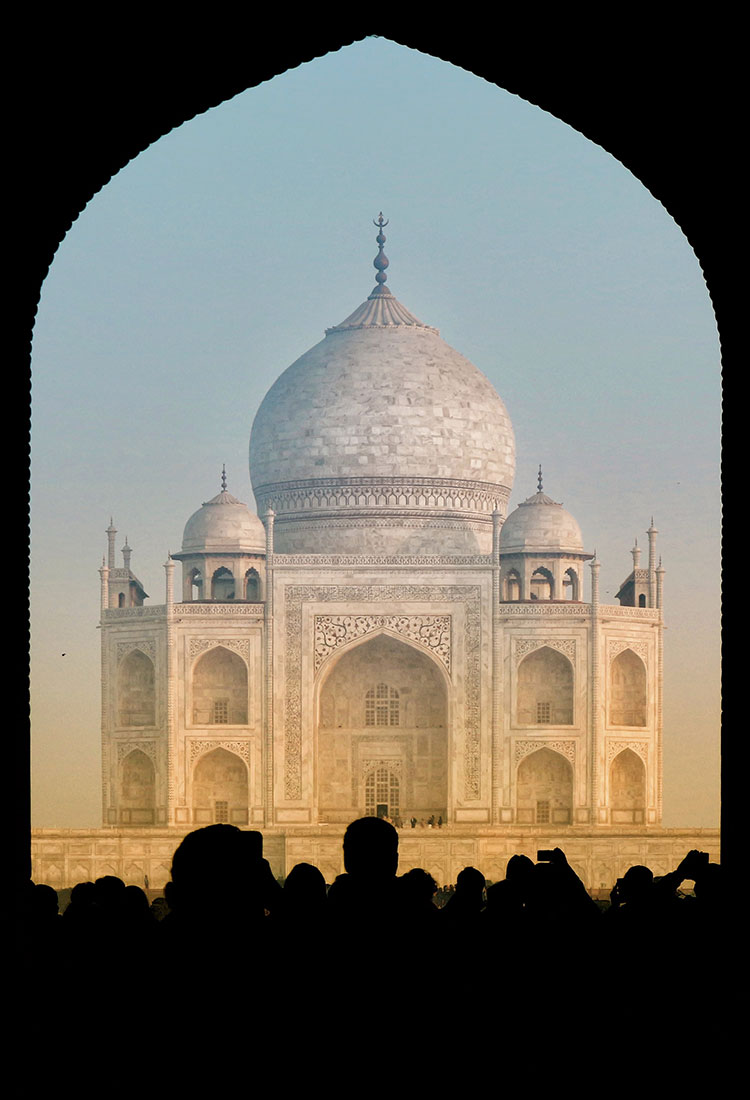

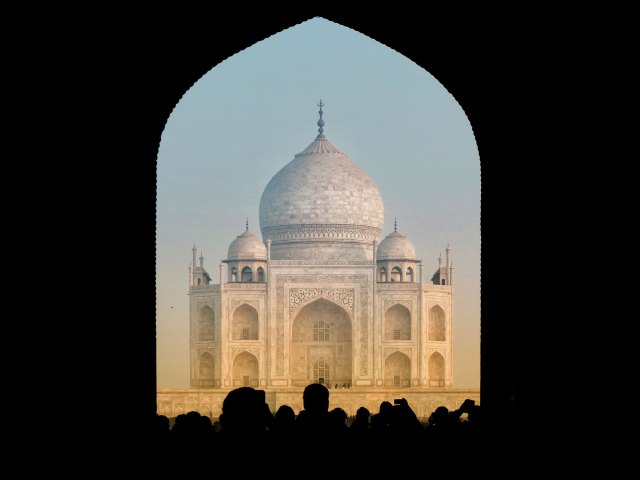

Taj Mahal – Agra, India

The Taj Mahal is widely known one of the most striking structures on Earth, designed as a mausoleum for Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s wife, Mumtaz Mahal, who was born Arjumand Banu Begum. Built from 1632 to 1648, the ethereal structure made of white marble is filled with contrasts when it comes to the gravesite itself. The graves of Mahal and Emperor Jahan himself are the only part of the mausoleum that are comparatively plain and dark in appearance since Muslim law prohibits graves from expressing vanity.

As a layer of protection, the four 130-foot-tall minarets on opposing sides of the building also stand at a slight angle to fall away from the tomb, should they collapse. While the Taj Mahal has a reputation for being perfectly symmetrical, there is one asymmetrical detail: The casket of Mahal is placed in the center of the crypt, but the casket of Jahan was placed slightly off-center when he was buried in 1666.

Colosseum – Rome, Italy

The massive ancient Roman Colosseum, officially named the Flavian Amphitheater, once seated 50,000 spectators and is best known for hosting the gladiator games — when combatants would fight to the death against each other or wild animals. But the entire stadium also hosted naval battle reenactments in which scaled-down battleships engaged in warfare in the flooded arena that was up to five feet deep.

To prepare for these nautical shows, stagehands would first remove the amphitheater’s floor and wood supports before the flooding began via a complex system of 40 aqueducts. Historians believe these aqueducts allowed a capacity of roughly two Olympic-sized swimming pools to enter the stage. Impressively, the four drains were able to remove the water in less than an hour.

Leaning Tower of Pisa – Pisa, Italy

Built over 800 years ago, the wayward tower, located about 90 minutes east of Florence, is losing its famed tilt. In 2018, it was reported that the Leaning Tower of Pisa was standing roughly 1.5 inches straighter than it had been for over the past 17 years. The newfound stature has been a long but careful process employed by a preservation team working to ensure that the 185-foot-tall white marble structure, which was designed as a bell tower for the city’s cathedral complex, doesn’t topple over. Before the preservation team began working on the structure, the tower was a whopping 13 feet off-center, which is equivalent to a six-degree tilt. Experts now believe that the leaning tower will be able to last another 200 years.

Sydney Opera House – Sydney, Australia

With its mammoth sails made of 1 million roof tiles, the Sydney Opera House — situated on Bennelong Point in the harbor — is one of the most recognizable silhouettes on Earth. A design contest to decide the look of the new opera house was held in 1956 in which 233 designs were considered before judges announced Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s blueprints as the winning entry. Construction on the opera house, which was only supposed to take four years, started in 1959, but wasn’t completed for more than a decade.

In 1960, the first performance in the opera house technically took place, when American singer Paul Robeson climbed up the scaffolding and sang his song “Ol’ Man River” to construction workers during their lunch break. The performance venue was eventually opened during a ceremony attended by Queen Elizabeth II in 1973.

Gateway Arch – St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.

At a glance, St. Louis’ trademark 630-foot-tall Gateway Arch is a structure of simplicity — a singular arch rising above the banks of the Mississippi River. However, its construction was a feat of architectural mastery, where precision — down to 1/64th of an inch — mattered. The two legs of the arch are equilateral triangles that start 54 feet wide at the bottom and taper to 17 feet wide at the top. The pieces, which were brought in on a train from Pennsylvania, are double-walled and filled with concrete up to the 300-foot mark, where they’re reinforced with steel stiffeners.

Architect Eero Saarinen’s winning design was completed in 1965 for $13.4 million. Two years later, the $2 million tram system inside opened, which allows visitors to ride up the curved arch in four minutes. If the arch ever feels like it’s a bit shaky, it’s because it was meant to sway up to 18 inches to withstand both strong wind and earthquakes. The foundations stretch 60 feet downward into the ground to ensure support.

Washington Monument – Washington, D.C.

As the centerpiece of the nation’s capital, the monument to honor the first president came from plans spurred on by the Washington National Monument Society, which formed in 1833 and included fourth President James Madison and fourth Chief Justice John Marshall. Initially, the Washington Monument was designed as a rotunda with a statue of President George Washington in a chariot — similar to many glorified Roman sculptures.

Alongside the chariot would be 30 other Founding Fathers. Eventually, the simple, 555-foot-tall obelisk was chosen instead, and it was the tallest building in the world when it opened in 1885. But perhaps the most impressive feature of the monument is that no mortar was used at all in its construction, as its marble blocks are simply held together using gravity and friction.

Space Needle – Seattle, Washington, U.S.

A fire burning from the top of Seattle’s most iconic structure? Indeed, that’s the way the Space Needle debuted on April 21, 1962, at the World’s Fair. The mast at the top of the tower had a natural gas torch called the Needle of Flame that lit up in rainbow colors. The Space Needle cast a blaze that was 40 to 50 feet tall and operated as a clock that turned every 15 minutes.

However, the torch wasn’t very energy-efficient since the fuel used to power the flame could heat 125 homes. It was removed from the tower when the fair ended. In addition to its fiery debut, the Space Needle also had a rainbow appearance, featuring an “Astronaut White” tower, “Orbital Olive” core, “Re-Entry Red” halo, and “Galaxy Gold” top (which had more of an orange sheen to it).

Liberty Bell – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

While the Liberty Bell is known for its famous crack, the story behind the bell’s damage is unknown, though theories abound. Once known as the State House Bell when it was located in the Pennsylvania State House, the London import, which was ordered in 1751, cracked the first time it was rung. Metalworkers John Pass and John Stow then melted the iron in Philly, before it was recast and put to use.

But by the 1840s, the crack started forming — believed to be from usage. In an attempt to fix it ahead of Washington’s birthday in 1846, the repair went wayward as a second crack appeared. While the story seems likely, the true explanation of how the crack came to be is a mystery. The bell’s damage means that no one alive today has ever heard it ring.

Stonehenge – Wiltshire, United Kingdom

As the world’s most mysterious prehistoric monument, there are more questions than answers about Stonehenge. But what is known about the famous stone circle is that it was erected in stages. First, there was an early monument on the site that was built about 5,000 years ago with an enclosure of about 328 feet with two entrances. About 56 pits called Aubrey Holes were also found from this period, though their purpose is uncertain.

Some think the holes may have held timber, while others believe they held stones. Then, in about 2500 BCE, the massive stones were brought in — large sarsens arranged in a horseshoe shape with an outer circle and smaller bluestones between them in an arc. The name Stonehenge likely comes from the Saxon term stan-hengen, which means “stone hanging.”

Mount Rushmore – Keystone, South Dakota

In the Black Hills of South Dakota, the faces of former Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln have been etched into history as Mount Rushmore, carved between 1927 and 1941 by 400 workers earning $8 a day. And behind Lincoln’s eyebrow is a secret chamber that its sculptor, Danish-American artist Gutzon Borglum, intended to be called the “Shrine of Democracy.”

With an 18-foot-tall doorway, the chamber measuring 75 feet long and 35 feet tall was supposed to contain an exhibit explaining the carvings so that future generations would know what the monument represented.

Featured image credit: Jandira Sonnendeck/Unsplash

More from our network

Daily Passport is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.