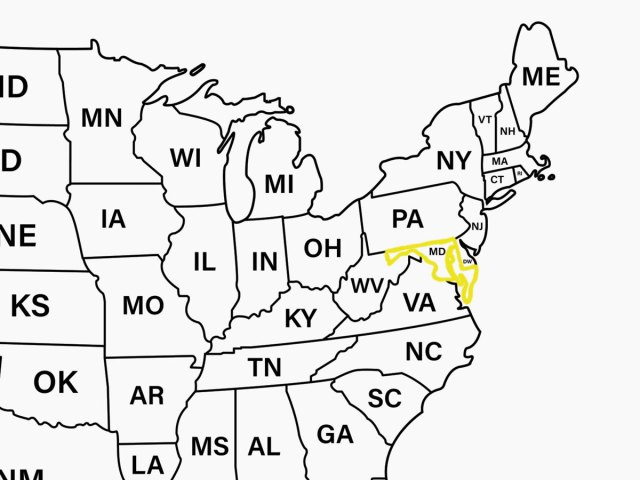

Take a closer look at a map of the U.S. and you’ll notice that, alongside the natural boundaries (rivers, for example) and the straight lines of some states, like those in the Great Plains, there are unexpected curves and other irregularities that seem to make little sense. While these boundaries may seem random, state borders have long been shaped by everything from history to geography to politics, leaving behind a patchwork of shapes. Here are six of the most strangely shaped states — and why they look the way they do.

Michigan

Michigan’s outline is instantly recognizable thanks to its Lower Peninsula, famously shaped like a mitten. But the state also has an Upper Peninsula that sits on its own, across the Straits of Mackinac, making Michigan the only state with two separate peninsulas. During the last ice age, massive glaciers carved out the Great Lakes and pulled the land apart, leaving the Straits of Mackinac where solid ground once was. (Glacier retreat and advances also carved out Michigan’s unmistakable mitten thumb.)

Michigan lays claim to the Upper Peninsula thanks to an unlikely trade. After the Toledo War of the 1830s, Ohio held on to Toledo, while Michigan was granted the Upper Peninsula in exchange, a swap that would later prove beneficial for Michigan. The region is home to some of the most valuable timber, iron, and copper deposits in the U.S.

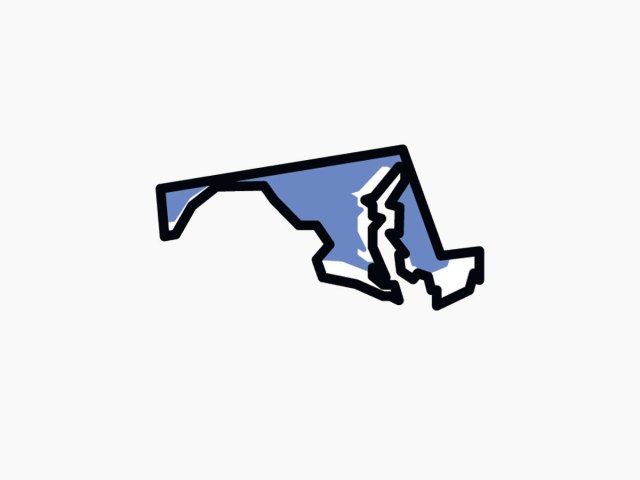

Maryland

Maryland is well known for blue crabs and the Chesapeake Bay, but its strange geographical shape is just as much a part of its identity. The Chesapeake cuts deep into Maryland, nearly splitting the state in two and leaving it stretched thin from east to west — with coastal edges that follow moving shorelines rather than straight lines.

The state was first chartered in 1632, and Maryland’s boundaries continued to be shaped by overlapping border claims and compromises over time. The western end of the state appears to be almost cut in half by West Virginia; in the north, it seems to cut into Pennsylvania. Maryland’s northern border was eventually settled by the Mason-Dixon Line, while the state’s narrow western panhandle, a mountainous rural area known as Western Maryland, exists to preserve access to the Potomac River, an important transportation route throughout the state’s history.

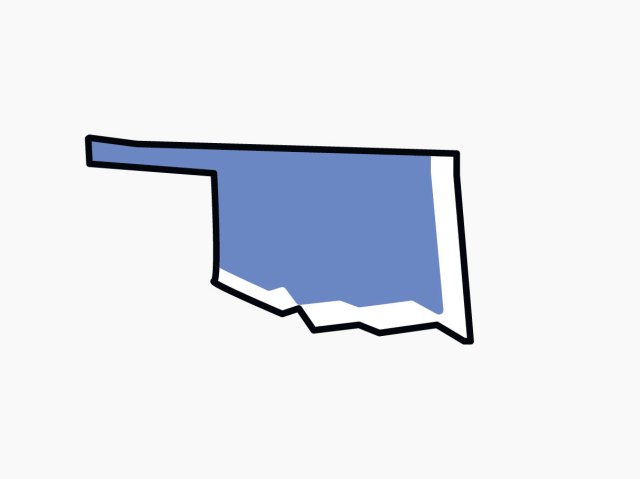

Oklahoma

Oklahoma’s panhandle closely resembles an actual pan handle jutting out from the state’s main body. This sliver of territory, about 166 miles long and just 34 miles wide, was left unclaimed after Texas set its northern border as part of the Compromise of 1850, a boundary beyond which slavery was prohibited, and Kansas shifted its border north in 1854.

For decades, the strip belonged to no state or organized territory at all, which led to its historical nickname of “No Man’s Land.” In 1890, the panhandle was formally incorporated into the Oklahoma Territory, and today travelers visit this westernmost part of the state looking for the highest point in Oklahoma (Black Mesa) or the No Man’s Land Museum to explore the region’s past.

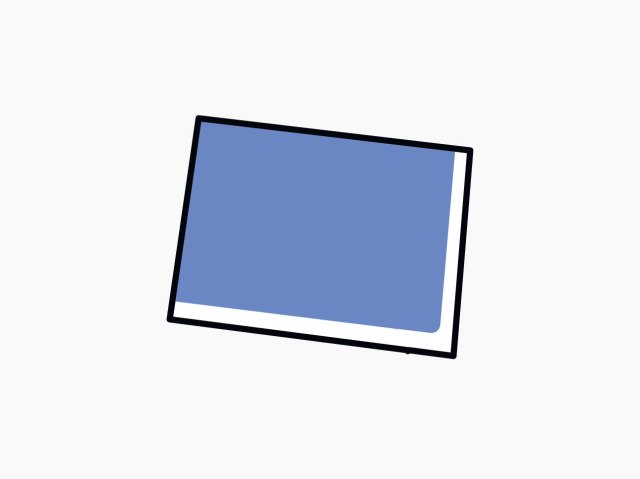

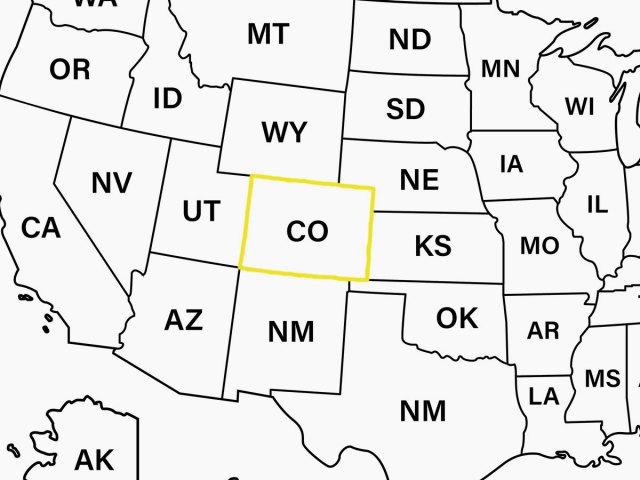

Colorado

At first glance, Colorado looks like a nearly perfect rectangle, but a closer inspection reveals more irregularly defined sides — 697 of them, to be exact. In 1876, Congress defined Colorado’s borders using lines of latitude and longitude. When surveyors finally marked the boundaries on the ground by hand in 1879, however, limited tools and difficult terrain led to many small inaccuracies that left the state with hundreds of subtle bends rather than four straight sides.

The most famous of these appears at the Four Corners, where Colorado meets Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. The monument marks the point surveyors actually set, not the precise coordinates Congress intended — they were off by several hundred feet but were later upheld as correct.

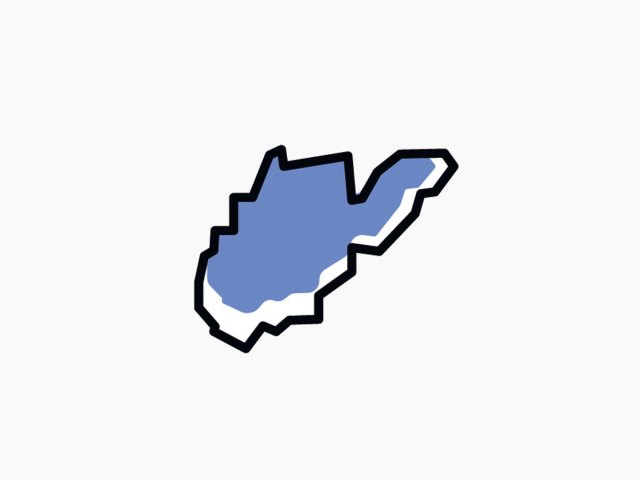

West Virginia

West Virginia’s shape is the product of one of the most significant state border changes in U.S. history. When Virginia voted to secede from the Union in 1861, its mountainous western counties broke away in opposition. The region organized its own government and was admitted to the Union as West Virginia in 1863, the only state to form by separating from a Confederate state.

The new borders followed existing county lines primarily shaped by the Appalachian Mountains, giving West Virginia its jagged outline. The distinct eastern panhandle was also made part of the new state so the Union could maintain control over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. West Virginia’s visual anomalies don’t stop there: Its thin sliver of land making up the northern panhandle, which resembles a finger between Ohio and Pennsylvania, is left over from historical land disputes with Pennsylvania over the Ohio River Valley.

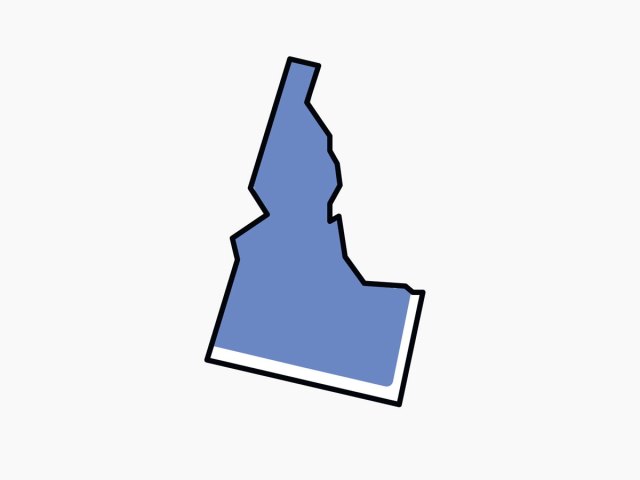

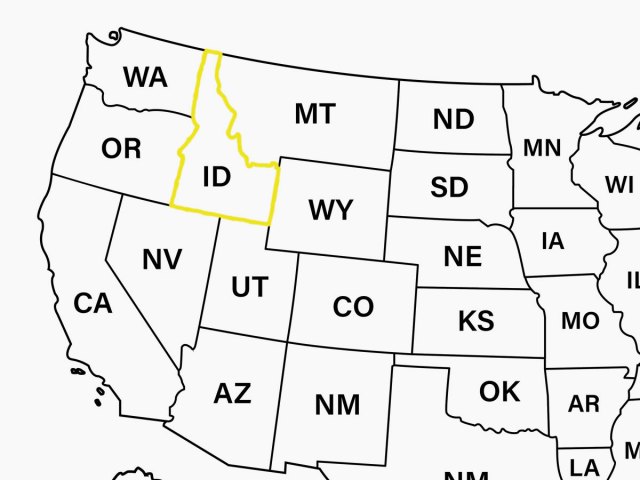

Idaho

Idaho’s shape has been described as a logger’s boot, a fist with the index finger pointing up, or even a gnome sitting in a chair. When the Idaho Territory was created under President Lincoln in 1863, the boundaries included not only today’s Idaho but also all of today’s Montana and most of Wyoming.

A year later, Montana split off, a decision driven by gold rushes, a surge in population, and the challenges of governing the region from Idaho’s capital of Lewiston in the west. Montana’s border was drawn along the rugged Bitterroot Mountain range, while the borders of Wyoming, created by Congress in 1868, were set as straight lines for simplicity.

And what about Idaho’s pointy northern panhandle? Interestingly, there’s no natural reason for it to exist. It was instead a strategic move by 19th-century surveyors largely meant as a political compromise. The narrow and isolated panhandle squeezes its way up between Washington and Montana, where the picturesque town of Bonners Ferry shares a border with the Canadian province of British Columbia.

More from our network

Daily Passport is part of Inbox Studio, an email-first media company. *Indicates a third-party property.