Though many visitors to Paris are drawn to iconic landmarks such as the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre, beneath the city’s bustling streets lies a hidden world that holds important pieces of the city’s past. The Catacombs of Paris — originally quarries dating back to the Roman era — are an extensive network of tunnels beneath the city that became a solution to Paris’ overcrowded cemeteries in the 18th century, housing the remains of some 6 million Parisians. Over the years, this unique underground site played a part in the French Revolution and World War II, served as a link in the food chain, and today, has become a secret playground for the adventurous. Discover the fascinating history of one of the City of Light’s most unique attractions with this in-depth guide to the Catacombs of Paris.

When the Catacombs Were Quarries

Approximately 45 million years ago, the site of modern-day Paris was submerged underwater, leaving sediment that, over time, turned to limestone. When Romans occupied the banks of the Seine River and founded the settlement of Lutetia around 52 BCE, they dug open-pit quarries and used the rock for monuments and other structures. Over time, these quarries were abandoned — but not forever.

By the Middle Ages, Paris was expanding, and its development once again relied heavily on the limestone from the quarries. By that time, they snaked far underground in networks that totaled over 200 miles of subterranean tunnels. As the city continued to grow, mining moved to the outskirts. The Paris mines, abandoned once again, began to pose structural risks to the urban landscape.

In December 1774, a stretch of street almost 1,000 feet long collapsed, taking homes and buildings with it. To stabilize the hollow grounds and save more of the city from sinking, King Louis XVI hired architect Charles Axel Guillaumot to inspect, map, and stabilize the quarries. Ceilings were raised, walls were reinforced, and even more tunnels were dug to connect the existing networks. It was a major undertaking, but Guillaumot and his team’s work underneath the city streets was far from finished.

Solving a Cemetary Crisis

By the mid-1700s, the Les Halles neighborhood of Paris faced a particularly disturbing issue. The largest cemetery in the city — the nearby Holy Innocents cemetery (also known as Saints Innocents) — had run out of space for the deceased. Overcrowded and often shallow graves caused corpses to resurface, exposing the living to not only unwelcome sights and smells but also the potential spread of disease.

In 1763, King Louis XV attempted to slow the overcrowding by banning burials within the city. However, resistance from the Catholic Church hindered any further progress in dealing with the growing public health problem. The issue lingered for years before coming to a head in 1780. After heavy spring rains destroyed a portion of a wall around Les Innocents, decomposing corpses spilled onto nearby properties. King Louis XVI closed the cemetery for good — it was now crucial that the city find a solution.

Remains Go Subterranean

In the wake of the cemetery crisis, the city decided to rehome its former residents’ remains in the empty underground quarries. Beginning in 1785, the bones from Holy Innocents’ tombs, mass graves, and charnel house were moved through a mine shaft in the Tombe-Issoire region to the new ossuaries located 65 feet underground. The remains were transported discreetly, primarily at night, to avoid public outcry and further church opposition.

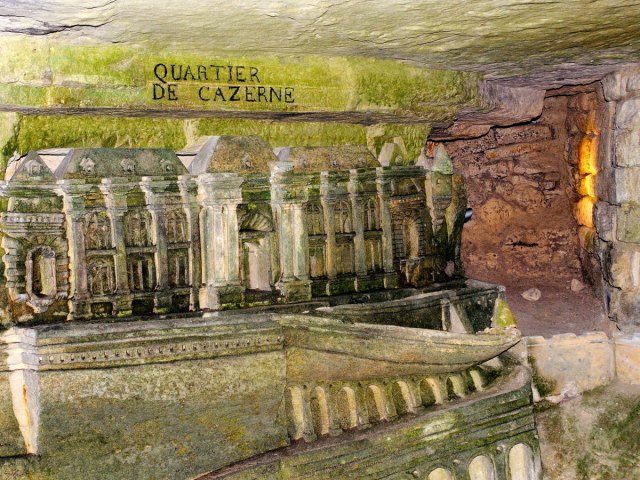

The process of transferring remains from various cemeteries continued over the following years. They were deposited by wagon into quarry wells, and quarry workers loosely organized them within the underground galleries. (Later, under the leadership of Paris mine inspector Héricart de Thury, they were rearranged into the artful displays seen today.) During the French Revolution, bodies were even buried directly underground. The transfers from the city’s cemeteries continued throughout the 1800s; remains ceased being moved into the ossuaries in 1860.

Though the new underground graveyard was formally dubbed the Paris Municipal Ossuary in 1786, the site adopted its now-iconic name shortly after, drawing inspiration from the Roman catacombs. In total, the remains of 6 to 7 million individuals were methodically moved to their final resting place in the Catacombs of Paris.

Stories, Secrets, and Secondary Uses

For at least as long as the Catacombs have been open to the public, the site has been the subject of mystery and intrigue. Over the years, myths and legends about secret societies, talking walls, and missing people have circulated, contributing to the allure of this eerie historical site.

One enduring tale involves the fairly recent discovery of a video camera. In 2010, the device was found with footage from the 1990s of a man who became lost while wandering through the tunnels. Another legend suggests that a man named Philibert Aspairt haunts the Catacombs. In 1793, he was working as a hospital doorman during the French Revolution when he allegedly disappeared into the catacombs without a trace.

The mazes of tunnels have also been a hiding spot for the French Resistance during World War II, a brewery, a mushroom farm, a Hollywood movie set, and the site of illegal dinner parties, concerts, and film screenings. In 2015, vacation home rental company Airbnb even offered a Halloween night stay in the ossuary.

How to Visit the Catacombs Today

While the Catacombs of Paris initially opened to the public in 1809 by appointment only, today they’re one of the most popular tourist attractions in the city, welcoming over 500,000 visitors every year. Tickets can only be purchased online, up to seven days in advance and by reserving a specific time slot.

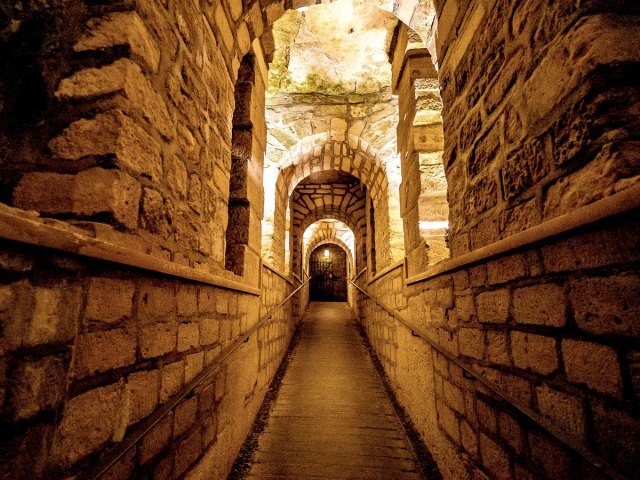

The entrance to the Catacombs can be found in a small, green building at Place Denfert-Rochereau. To start, you’ll descend 131 steps, then proceed with a 15-minute walk to the ossuary. As you make your way through the dimly lit, narrow hall, you’ll be able to see street names, sculptures, and historical information, before finally making it to the remains, which are artfully arranged into several sections of awe-inspiring skeleton sculptures. The tour lasts about an hour, after which you’ll walk back up 112 stairs to resurface on Avenue René-Coty.

The Catacombs are kept at a constant temperature of 57 degrees Fahrenheit. It is recommended to dress in light layers that can be carried easily if need be (there is no coat check). Due to the small, dark, and damp nature of the space, the Catacombs are not wheelchair accessible and are not recommended for people with motor ability constraints, cardiac or respiratory issues, or for pregnant individuals. Children under 13 must be accompanied by an adult, and no strollers can be taken in.

And of course, touching the bones is expressly forbidden. They’re not only fragile — but they are also human remains, not decorations, and warrant respect and care. Indeed, the Catacombs and its inhabitants are a testament to the history and geology of Paris and a reminder of the transience of life. A visit should be on every tourist’s agenda.

More from our network

Daily Passport is part of Inbox Studio, an email-first media company. *Indicates a third-party property.